LENA CAMELINA

LENTZ RESURGENT GRAINS have a tiny yet compelling companion, not a grain but an ancient oilseed, Camelina sativa. Camelina’s center of origin is Armenia, where earliest archeological evidence points to the sixth millennium B.C. The wild form of Camelina there was Camelina microcarpa, a member of the Brassica family.

Bordering on Turkey, Armenia lies near the region where the Ur-grain Einkorn originated. Which explains why Camelina became a little hitchhiker when Einkorn and Emmer seed, and some pulse crops, too, were carried together to Europe’s new farmlands. Yes, our Camelina began as traveling weed seed – a tiny seed, around 350,000 seeds per pound. This hitchhiking of course happened after grains and Camelina had found a propensity for growing together, speak: coevolution. In the very earliest agriculture of central and northern Europe it was common to raise grains and pulses together; they’re stored together in underground silos. Eventually Camelina was domesticated, its first crop use as oil dates in the younger Neolithic. The younger Bronze Age (1200 BC) was the heyday for Camelina sativa. When the Celts fought along Donau and Rhine in fifth century B.C., Camelina was celebrated as the Oil of the Celts. Mischkultur – the growing of several crops intermingled in a field – still was common practice. Since 800 B.C., European oil crops had included hemp, poppy, flax, yet Camelina clearly held sway in importance especially in coastal regions, perhaps due to the fact that the crop is relatively salt tolerant. The Romans used Camelina as edible oil and also as lamp oil. Thus Camelina retained its stature as major crop for centuries, but after the Roman occupation of Gaule the grand era of Camelina came to an end. No one knows why – one theory has it that the expanding Roman trade in olive oil was one of the causes. Still, Camelina continued to be raised widely for its oil, albeit as minor crop. In the Middle Ages a species called Camelina allysum spread into flax fields, growing there as companion crop just as Camelina sativa grew in fields of hulled grains. A number of healers explained medicinal benefits of Camelina oil; in 1546, Hieronymus Bock praised Saarland Camelina oil as lieblich – “dear, lovely” – in his botanical writings. From Siberia and other parts of Asia, to Central Europe and Spain, Camelina was a trusted crop until industrialization gave it the thumbs-down – ironically because Camelina oil does not lend itself to hydrogenation. Public outcry over transfats was exactly what led to the resurgence of Camelina. European scientists ascertained a high omega 3 content in Camelina, as well as high levels of the rare antioxidant vitamin E, gamma tocopherol. Organic growers in Germany, Austria, France, Poland and Russia re-learned Camelina agronomy, including the Mischkultur practice of intermingling companion crops. Various folk names indicate Camelina’s former glory: Leindotter, German Sesame, Gold-of-Pleasure, Wild Flax, Siberian Oil Seed. Since the resurgence, those old names pop up in the market again, on labels of salad oils and skin care products. Lena Camelina is a blend of two Camelina varieties approved for food use in Europe. Lena Camelina Seed is a popular item on the shelf next to flax seed and chia seed. Chefs enjoy the aromatic motif Lena Camelina Oil lends their fresh salads, a reminder for the palate how coevolution and Mischkultur adds color for the taste buds. > Sources: Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives, France; Bundesverband Pflanzenöle e.V., Germany; Montana State University < |

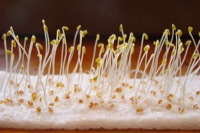

Lena Camelina sprouts during a germ test

Early growing stage of Lena Camelina

Early bloom of Lena Camelina

Lena Camelina seed in the hopper of the

combine at harvest First Camelina Mischkultur in

Washington State: Camelina planted intermingled with Emmer Farro |