For a printable version of newsletter click here.

INTERLUDE: COLONIALISM

Our timeline has arrived where ever more periods overlap, and even if we’re just drawing a sketch of civilization – speak: agriculture and its overpopulation effect – we must wrap our minds around colonization after Christopher Columbus’ so-called discovery of America in 1492.

This puts us in a bind – where do we leave Lena Lentz Hardt? She’s traveled from her Lentz Spelt Farms on the Columbia Plateau to Germany, to see with her own eyes where her forebears farmed before emigrating to Catherine the Great’s Russia. But Germans, among them the Lentz progenitors, did not sail to conquer the New World. While Spain and Portugal, England and the Netherlands established their overseas colonies and thus grew into global empires, the Germans were busy killing one another over religious differences in a long series of almost continuous bloodshed.

Colonizing the New World meant new crop plants coming to Europe, potato and maize the most important ones. But rural Germans retained for their main staple foods rye and spelt and some wheat.

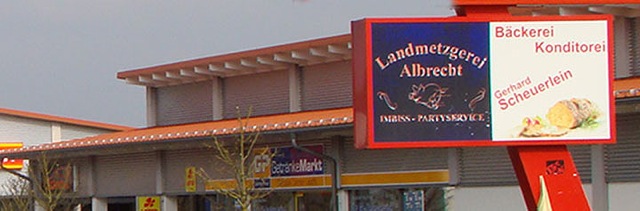

Which gives us the idea that we should leave Lentz where those grains rule to this day, at the Bäckerei, the bakery with its Bienenstich and Käsekuchen, Nussschnecken and Krapfen. As American Lentz stands out, of course, there in the queue of Frau and Fräulein with their woven baskets they use for local shopping. The girls behind the counter of the big glass case make busy cutting cake, wrapping each slice neatly; they bag rolls and reach behind them for bread from the grand parade of loaves on tall wooden shelves.

Lentz stands in the bustle of German greetings and thank you’s and coins a-jingling on the flat bowl set on the counter for that purpose. Hot breath of bakery aroma sidles in from the back to dissipate among skirt rustle and the click of high heels on worn wood floor. A few old gents sip coffee at the tables by the window. Yes, a German bakery is a busy place.

Now it’s Lentz’s turn. She points, communicating with the sales girl by eye and hand. Everything in the big case looks so good, so sweet, so dessert. She points again, the girl repeating her gesture as from a mirror. When the girl rings up the purchase, Lentz fishes around in her purse – she’s still learning the Euro bills and coins.

Lentz got to really like the bakery across the street from where she’s staying. “The bakery was one place where I could go in and not get lost,” she recalls, remembering the labyrinthine layout of some German markets. “Being in the bakery was fun. I recognized hardly any of the baked stuff. It was always a you’re-not-in-Kansas-anymore kind of experience. Everything in the case was fresh! Whatever looked good, that’s what I bought.”

Our timeline has arrived where ever more periods overlap, and even if we’re just drawing a sketch of civilization – speak: agriculture and its overpopulation effect – we must wrap our minds around colonization after Christopher Columbus’ so-called discovery of America in 1492.

This puts us in a bind – where do we leave Lena Lentz Hardt? She’s traveled from her Lentz Spelt Farms on the Columbia Plateau to Germany, to see with her own eyes where her forebears farmed before emigrating to Catherine the Great’s Russia. But Germans, among them the Lentz progenitors, did not sail to conquer the New World. While Spain and Portugal, England and the Netherlands established their overseas colonies and thus grew into global empires, the Germans were busy killing one another over religious differences in a long series of almost continuous bloodshed.

Colonizing the New World meant new crop plants coming to Europe, potato and maize the most important ones. But rural Germans retained for their main staple foods rye and spelt and some wheat.

Which gives us the idea that we should leave Lentz where those grains rule to this day, at the Bäckerei, the bakery with its Bienenstich and Käsekuchen, Nussschnecken and Krapfen. As American Lentz stands out, of course, there in the queue of Frau and Fräulein with their woven baskets they use for local shopping. The girls behind the counter of the big glass case make busy cutting cake, wrapping each slice neatly; they bag rolls and reach behind them for bread from the grand parade of loaves on tall wooden shelves.

Lentz stands in the bustle of German greetings and thank you’s and coins a-jingling on the flat bowl set on the counter for that purpose. Hot breath of bakery aroma sidles in from the back to dissipate among skirt rustle and the click of high heels on worn wood floor. A few old gents sip coffee at the tables by the window. Yes, a German bakery is a busy place.

Now it’s Lentz’s turn. She points, communicating with the sales girl by eye and hand. Everything in the big case looks so good, so sweet, so dessert. She points again, the girl repeating her gesture as from a mirror. When the girl rings up the purchase, Lentz fishes around in her purse – she’s still learning the Euro bills and coins.

Lentz got to really like the bakery across the street from where she’s staying. “The bakery was one place where I could go in and not get lost,” she recalls, remembering the labyrinthine layout of some German markets. “Being in the bakery was fun. I recognized hardly any of the baked stuff. It was always a you’re-not-in-Kansas-anymore kind of experience. Everything in the case was fresh! Whatever looked good, that’s what I bought.”

Photo by Gabi Grau

Photo by Gabi Grau Bienenstich (“Sting of the Bee”): vanilla creme on a layer of dough, topped with caramelized sugar and almond slivers.

Käsekuchen (Cheese Cake): sweet creamed cheese on a rough dough, raisins.

Nussschnecken (yes, three ‘S’ next to each other, “Nut Snails”): soft dough fashioned like a spiral snail shell with soft, sugary nut-filling.

Krapfen: as it happens, Lentz visits Germany when Franconia goes Krapfen-crazy; Krapfen are similar to American donuts (without the hole), but the fried dough is more robust and has more crumb structure; in the weeks of Fastnacht (Mardi Gras) it’s tradition to fill the Krapfen with delicious jam, and everyone has to eat at least one.

Lentz looks for a free table and carries her coffee and the sweet treats there – which one should she eat first? –, while we disappear into the fog of colonialism.

Käsekuchen (Cheese Cake): sweet creamed cheese on a rough dough, raisins.

Nussschnecken (yes, three ‘S’ next to each other, “Nut Snails”): soft dough fashioned like a spiral snail shell with soft, sugary nut-filling.

Krapfen: as it happens, Lentz visits Germany when Franconia goes Krapfen-crazy; Krapfen are similar to American donuts (without the hole), but the fried dough is more robust and has more crumb structure; in the weeks of Fastnacht (Mardi Gras) it’s tradition to fill the Krapfen with delicious jam, and everyone has to eat at least one.

Lentz looks for a free table and carries her coffee and the sweet treats there – which one should she eat first? –, while we disappear into the fog of colonialism.

*****

The colonized were peoples with less powerful technology than the colonizers possessed. Some colonized had civilizations of their own, but many were indigenous in the sense that they lived how humans had lived for a half a million years, in small bands, in and of nature, foraging edible roots, forbs, fruits, and hunting and fishing.

In most cases those tribal societies were eradicated, many killed outright, others disappeared into peripheral existence when their culture was usurped, their way of nomadic life having become impossible. Almost always agriculture was the root of the evil, because the lands of good gathering and hunting were invariably also the most fertile farmlands, and the first to be seized by the colonial powers.

For this reason indigenous cultures were most likely to survive in what are marginal regions from the farming perspective. The largest of those marginal regions, some call it the Fourth World, forms a circle around the North Pole: the immense lands above the Polar Circle.

That’s where we’re heading, into the realm of midnight sun, northern lights. We want to see how colonization is playing out these days.

The far north of Fennoscandia (Scandinavia plus Finland and the Kola Peninsula of Russia) is still labelled Lapland on most maps. We drive north through the middle of Sweden, and a long drive it is as the towns get smaller and the distances of forest more and more expansive. Tourists venture to Lapland enthralled by “Europe’s last wilderness.”

There is no arguing with the fact that Lapland is a wild place dominated by nature. But it’s also the homeland of a great people who call themselves the Sámi. So quit thinking Lapland already. We are in Sápmi.

We alight in Abisko National Park west of Kiruna in Swedish Sápmi, camping in a forest of dwarf birch. Nowhere else we’ve been does nature revel in such vigor, such intensity. It’s early June and the leaves on the birches are just unfolding from their buds, the grasses have just begun to sprout anew, and they push forth at an unimaginably rapid growth rate. Every single day, outside the tent flap we see a centimeter and more of plant growth since the previous morning!, such is the botanical response to the wash of 24-hour sunlight. Along the path blossoms appear on plants that had emerged from the soil but a few days ago. We speak with a young man tending the tiny chef’s garden at the Park lodge: “Everything grows way faster here,” he says, nodding at the vegetable beds. “It’s amazing how fast.”

Yet the weather is unpredictable: three days before the summer solstice, storms strew snow onto our little tent.

In most cases those tribal societies were eradicated, many killed outright, others disappeared into peripheral existence when their culture was usurped, their way of nomadic life having become impossible. Almost always agriculture was the root of the evil, because the lands of good gathering and hunting were invariably also the most fertile farmlands, and the first to be seized by the colonial powers.

For this reason indigenous cultures were most likely to survive in what are marginal regions from the farming perspective. The largest of those marginal regions, some call it the Fourth World, forms a circle around the North Pole: the immense lands above the Polar Circle.

That’s where we’re heading, into the realm of midnight sun, northern lights. We want to see how colonization is playing out these days.

The far north of Fennoscandia (Scandinavia plus Finland and the Kola Peninsula of Russia) is still labelled Lapland on most maps. We drive north through the middle of Sweden, and a long drive it is as the towns get smaller and the distances of forest more and more expansive. Tourists venture to Lapland enthralled by “Europe’s last wilderness.”

There is no arguing with the fact that Lapland is a wild place dominated by nature. But it’s also the homeland of a great people who call themselves the Sámi. So quit thinking Lapland already. We are in Sápmi.

We alight in Abisko National Park west of Kiruna in Swedish Sápmi, camping in a forest of dwarf birch. Nowhere else we’ve been does nature revel in such vigor, such intensity. It’s early June and the leaves on the birches are just unfolding from their buds, the grasses have just begun to sprout anew, and they push forth at an unimaginably rapid growth rate. Every single day, outside the tent flap we see a centimeter and more of plant growth since the previous morning!, such is the botanical response to the wash of 24-hour sunlight. Along the path blossoms appear on plants that had emerged from the soil but a few days ago. We speak with a young man tending the tiny chef’s garden at the Park lodge: “Everything grows way faster here,” he says, nodding at the vegetable beds. “It’s amazing how fast.”

Yet the weather is unpredictable: three days before the summer solstice, storms strew snow onto our little tent.

Abisko National Park impresses with its environmental sensitivities. Well-marked trails fan out, some of them even have designated meditation points (that was a new one on us). Where the trails cross bogs, boardwalks keep hikers from disturbing the delicate ground cover. Designated campsites nestle at least-impact locations. A few areas are off-limits during the breeding season of rare birds. Ah, the birds, now that we’ve experienced the seasonal magnitude of nature at these latitudes, we understand why so many birds fly thousands of miles to breed in the arctic. The Park boasts that over 200 bird species enliven the summers here.

In the visitors center, displays inform about the various animals on the fell. We learn what enables reindeer to live through the long and dark arctic winters, namely that they can survive on lichen after they stock up on more nutritional feed during the bright months when they graze on as many as 250 plant species. For the winter snow cover evolution gave them large hooves, and a keen sense of smell to detect the lichen beneath the snow. But biologists cannot explain the tendon over a bone in the hind foot that emits a clicking sound when reindeer walk, perhaps it’s an auditory help in finding the herd? When the herd runs it’s always with the head into the wind. The last wild reindeer in Sweden was shot in the late 19th century; today 230,000 reindeer graze on herding areas that make up 40 percent of Sweden’s land mass; they’re owned by 4500 Sámi.

Male reindeer weights range from 100 to 150 kilograms, does weigh between 60 and 90 kilograms.

The reindeer’s rare ability to digest lichen became a factor after the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986, because lichen soaks up radiation and holds it for a long time. In Swedish Sápmi the meat from over 30,000 reindeer had to be buried, and in the years following, the slaughter period had to be moved up to before the reindeer begin eating lichen. The Chernobyl incident and its aftermath demonstrated how an industrial catastrophe quite far away can have devastating impacts on a fragile arctic.

One section of the Park’s visitors center offers educational material about Sámi history and culture, which is treated with due respect. A short walk takes you to a small outdoor museum of Sámi traditions. A goahte is set up, the tipi-like dwelling that, covered with turf, served the Sámi as semi-permanent home; on their seasonal migration, when camp was made for shorter periods, the goahte poles were covered with skins.

Other structures on the Abisko site are various traditional cache constructions, nifty ways of building high off the ground to protect food stuff.

Later we visit a similar outdoor museum near Kiruna where boat-like reindeer sleds lie in a shelter. The very earliest skis must have been a miniature version of those sleds.

Living in nature, the Mountain Sámi went on long journeys following the reindeer they hunted; the Forest Sámi also moved seasonally, but their reindeer migrated along shorter routes.

In the visitors center, displays inform about the various animals on the fell. We learn what enables reindeer to live through the long and dark arctic winters, namely that they can survive on lichen after they stock up on more nutritional feed during the bright months when they graze on as many as 250 plant species. For the winter snow cover evolution gave them large hooves, and a keen sense of smell to detect the lichen beneath the snow. But biologists cannot explain the tendon over a bone in the hind foot that emits a clicking sound when reindeer walk, perhaps it’s an auditory help in finding the herd? When the herd runs it’s always with the head into the wind. The last wild reindeer in Sweden was shot in the late 19th century; today 230,000 reindeer graze on herding areas that make up 40 percent of Sweden’s land mass; they’re owned by 4500 Sámi.

Male reindeer weights range from 100 to 150 kilograms, does weigh between 60 and 90 kilograms.

The reindeer’s rare ability to digest lichen became a factor after the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986, because lichen soaks up radiation and holds it for a long time. In Swedish Sápmi the meat from over 30,000 reindeer had to be buried, and in the years following, the slaughter period had to be moved up to before the reindeer begin eating lichen. The Chernobyl incident and its aftermath demonstrated how an industrial catastrophe quite far away can have devastating impacts on a fragile arctic.

One section of the Park’s visitors center offers educational material about Sámi history and culture, which is treated with due respect. A short walk takes you to a small outdoor museum of Sámi traditions. A goahte is set up, the tipi-like dwelling that, covered with turf, served the Sámi as semi-permanent home; on their seasonal migration, when camp was made for shorter periods, the goahte poles were covered with skins.

Other structures on the Abisko site are various traditional cache constructions, nifty ways of building high off the ground to protect food stuff.

Later we visit a similar outdoor museum near Kiruna where boat-like reindeer sleds lie in a shelter. The very earliest skis must have been a miniature version of those sleds.

Living in nature, the Mountain Sámi went on long journeys following the reindeer they hunted; the Forest Sámi also moved seasonally, but their reindeer migrated along shorter routes.

*****

“We are still alive.” So writes Johan Utsi in The Sámi, People of the Sun and Wind. The small book was published on occasion of the Year of the Indigenous People, 1993, as proclaimed by the United Nations. Globally about 300 million indigenous people were counted in 1993. The Sámi numbered 70,000.

“We are still alive” – could one think of a more potent lead sentence? European ears may get an uneasy feeling of accusation as the words power up images of colonizers as heedlessly brutal as they were impervious to the fact that gun and religion do not make you a better human, more human. Just the opposite, for centuries.

“We are still alive” – could one think of a more potent lead sentence? European ears may get an uneasy feeling of accusation as the words power up images of colonizers as heedlessly brutal as they were impervious to the fact that gun and religion do not make you a better human, more human. Just the opposite, for centuries.

“Our own India!” was the Swedish aristocracy’s elation after valuable ore was discovered in Sápmi. Not exactly a gentle blueprint for the colonization of the Sámi whose ancestors had come to this raw land after a warming climate trend began to melt the last Glacial Age ice sheet over Fennoscandia, about 10,000 years ago.

They came from the east, following the reindeer.

By 4,200 BC the reindeer hunter culture found expression in stone carvings. “The continuity of the tradition of engraving in stone through thousands of years would seem to indicate that the same ethnic group lived (in Sápmi) during a long period of time,” writes Utsi.

They hunted reindeer and moose by digging deep pits where the migration routes of the reindeer narrowed; the earliest of these pits date back 6,000 years. This is indication of a society well organized, which organization developed into the system of sijdda that designated specific territory and hunting routes of a group of families, about 100 to 150 people each. Utsi describes “...consultations between sijdda groups, during which resources were divided...”

That they managed to tame reindeer shows a close relationship with nature. The taming of reindeer goes back at least 2000 years, although initially only a few reindeer were tamed to serve as decoys near the hunting pits.

The initial exchanges between the Sámi and traders from outside their region were peaceful. The Sámi liked silver artifacts in particular. Their own handicrafts – woven items, and bone and antler carvings – were eye-appealing, and of course they had furs and hides to trade as well.

When the tentacles of Scandinavian kingdoms began to encroach on Sápmi, as far back as in the Middle Ages, taxation was their big grab. “The taxes collected from the Sámi were of much greater value than (those) which the farmers of the coast could pay.” Tax demands by Sweden-Finland, Denmark-Norway, and Russia increased so much that the wild reindeer populations began to shrink. Reindeer numbers declined further when farmers were lured to the north – as elsewhere, it was thought that a settled population would help stabilize state boundaries –; farming in the arctic, however, was exceedingly difficult, and many settlers resorted to hunting reindeer for their survival. Of still further impact were Finnish farmers who burned forest in preparation for tillage, thereby eliminating valuable reindeer habitat.

The Sámi responded to the drastic reindeer population decline by becoming herders in the 16th century. Around that time they also began adding reindeer milk to their diet, a practice that has since stopped. Goats, too, were a new addition then, although never in great numbers.

They came from the east, following the reindeer.

By 4,200 BC the reindeer hunter culture found expression in stone carvings. “The continuity of the tradition of engraving in stone through thousands of years would seem to indicate that the same ethnic group lived (in Sápmi) during a long period of time,” writes Utsi.

They hunted reindeer and moose by digging deep pits where the migration routes of the reindeer narrowed; the earliest of these pits date back 6,000 years. This is indication of a society well organized, which organization developed into the system of sijdda that designated specific territory and hunting routes of a group of families, about 100 to 150 people each. Utsi describes “...consultations between sijdda groups, during which resources were divided...”

That they managed to tame reindeer shows a close relationship with nature. The taming of reindeer goes back at least 2000 years, although initially only a few reindeer were tamed to serve as decoys near the hunting pits.

The initial exchanges between the Sámi and traders from outside their region were peaceful. The Sámi liked silver artifacts in particular. Their own handicrafts – woven items, and bone and antler carvings – were eye-appealing, and of course they had furs and hides to trade as well.

When the tentacles of Scandinavian kingdoms began to encroach on Sápmi, as far back as in the Middle Ages, taxation was their big grab. “The taxes collected from the Sámi were of much greater value than (those) which the farmers of the coast could pay.” Tax demands by Sweden-Finland, Denmark-Norway, and Russia increased so much that the wild reindeer populations began to shrink. Reindeer numbers declined further when farmers were lured to the north – as elsewhere, it was thought that a settled population would help stabilize state boundaries –; farming in the arctic, however, was exceedingly difficult, and many settlers resorted to hunting reindeer for their survival. Of still further impact were Finnish farmers who burned forest in preparation for tillage, thereby eliminating valuable reindeer habitat.

The Sámi responded to the drastic reindeer population decline by becoming herders in the 16th century. Around that time they also began adding reindeer milk to their diet, a practice that has since stopped. Goats, too, were a new addition then, although never in great numbers.

Colonization intensified when Sweden was pressed for resources during the Thirty-Year War, at the same time as silver ore was discovered in Sápmi on the border between Sweden and Norway. In 1635 the Swedes began mining there; they forced Sámi reindeer herders to use their animals to haul the ore to the smelter, a distance of about 40 miles, and from there to the shipping harbor on the Gulf of Bothnia, a whopping 250 miles away. Although trained as draft animals, the reindeer were not cut out for such heavy-load long-hauls, and many died. Sámi left Sweden for Norway to escape the odious burden.

The Sámi system of agreeably divvying up their lands into sijdda was already long interrupted by this time. “Throughout history, the Sámi seem to have chosen their nationality tactically,” Utsi explains. “They have chosen to belong to the state which at the moment was most favorable for their source of livelihood. New boundaries have often resulted in the Sámi having to move, or changing their means of livelihood.”

The Sámi let themselves be baptized when missionaries showed up, usually accompanied by heavy-handed, armed enforcers. A prime objective of converting the Sámi was to get them on the tax rolls. But for a long time the Sámi were Christian in name only, persistently carrying on with their own spirituality that was interwoven with nature; the Sámi drum, complex in construction and painted with mythological symbols of the Three Worlds, was a sacred object in every home. Through the drum’s sounding they communicated with spirits and divined the future. At center of the community stood the shaman, the Noajdde: holy man, healer, keeper of traditions, observer of rites; the Noajdde drummed his way into a trance wherein he could change shape – in the spirit world – and invoke visions.

The witch hunts, which flared in Sweden by the end of the 17th century, set out to destroy Sámi faith and customs by forcing them to hand over their sacred drums; their Noajdde received punishment from flogging to being burned at the stake.

Most of the Sámi drums the missionaries burned, although, already in the 1600s, Europeans developed a fascination with Sámi culture, and a number of Sámi drums were taken as curios to faraway places such as Tuscany and Rome. Today, according to the Ájtte Swedish Mountain and Sámi Museum, a mere 70 of the sacred drums exist in museums and in private collections across the continent.

We get another perspective on his “We are still alive” theme in an essay Utsi wrote for the booklet Drum-Time. “A thought that sometimes strikes me is that we (Sámi) believe in the drum as a mirror of the soul. The world of the drum is still there in our dreams, hidden in our language and in our way of thinking and acting. Hidden little islands inside us that no-one has reached – yet.”

The Sámi system of agreeably divvying up their lands into sijdda was already long interrupted by this time. “Throughout history, the Sámi seem to have chosen their nationality tactically,” Utsi explains. “They have chosen to belong to the state which at the moment was most favorable for their source of livelihood. New boundaries have often resulted in the Sámi having to move, or changing their means of livelihood.”

The Sámi let themselves be baptized when missionaries showed up, usually accompanied by heavy-handed, armed enforcers. A prime objective of converting the Sámi was to get them on the tax rolls. But for a long time the Sámi were Christian in name only, persistently carrying on with their own spirituality that was interwoven with nature; the Sámi drum, complex in construction and painted with mythological symbols of the Three Worlds, was a sacred object in every home. Through the drum’s sounding they communicated with spirits and divined the future. At center of the community stood the shaman, the Noajdde: holy man, healer, keeper of traditions, observer of rites; the Noajdde drummed his way into a trance wherein he could change shape – in the spirit world – and invoke visions.

The witch hunts, which flared in Sweden by the end of the 17th century, set out to destroy Sámi faith and customs by forcing them to hand over their sacred drums; their Noajdde received punishment from flogging to being burned at the stake.

Most of the Sámi drums the missionaries burned, although, already in the 1600s, Europeans developed a fascination with Sámi culture, and a number of Sámi drums were taken as curios to faraway places such as Tuscany and Rome. Today, according to the Ájtte Swedish Mountain and Sámi Museum, a mere 70 of the sacred drums exist in museums and in private collections across the continent.

We get another perspective on his “We are still alive” theme in an essay Utsi wrote for the booklet Drum-Time. “A thought that sometimes strikes me is that we (Sámi) believe in the drum as a mirror of the soul. The world of the drum is still there in our dreams, hidden in our language and in our way of thinking and acting. Hidden little islands inside us that no-one has reached – yet.”

*****

The story doesn’t end with turning holy drums into ashes. If the arctic is an agriculturally marginal place, at best, it contains riches that industrialism is hungry for, including timber for the clear-cutting, minerals for the strip-mining, hydro-electric power harvested at huge dams, all projects that mar the land and destroy reindeer habitat in a big way.

“In the name of Lenin, God or Progress, indigenous people have been robbed and seduced,” Utsi accuses.

The legal basis for the exploitation is simple cant: according to the laws of Sweden, Norway and Finland, “hunters and fishers cannot own land,” Utsi points out. “The Swedish state now considers that the Sámi pay tax only for the use of the area, and that the state has always been the owner of the land.” At no point, he adds, have the Sámi ever sold their territory.

“In the name of Lenin, God or Progress, indigenous people have been robbed and seduced,” Utsi accuses.

The legal basis for the exploitation is simple cant: according to the laws of Sweden, Norway and Finland, “hunters and fishers cannot own land,” Utsi points out. “The Swedish state now considers that the Sámi pay tax only for the use of the area, and that the state has always been the owner of the land.” At no point, he adds, have the Sámi ever sold their territory.

But a new wind seems to be blowing. We cross into the Finnish part of Sápmi, and in Inari, where the Sámi parliament is located, we’re surprised by an exhibit of protest art from a long-drawn blockade that had happened the previous summer in Sweden where a mining company started up exploratory work. Our surprise was two-fold: you wouldn’t expect a demonstrators’ barricade to consist of so many pieces of art, and, even though it was a Sámi protest, many of the people who undertook this action against yet another mine were clearly not Sámi but environmentalists from all over the world, “No Nature, No Future” the catch phrase for all.

That the United Nations declares a Year of the Indigenous People is further indication of a growing sentiment against colonization in all its forms. Even in academia it’s accepted now that cultural diversity is important, ever more so in this age of globalization. To wit: the work of Juha Pentikäinen, since 1972 department chair of comparative religion at a Helsinki university, and also well-known as visiting professor at universities in California, Indiana, Minnesota, Texas. His extensive research investigates the circumpolar peoples in Sápmi and in the Russian arctic. He writes with an authoritative voice, having undertaken over 20 journeys to interview, and interact with, shamans, including one of the Khanty in Siberia when the weather was “cold” – minus 42 degrees Celsius.

In Shamanism and Culture (© 2006) Pentikäinen analyzes what Russia’s oil and gas industries are doing to indigenous lives and cultures, destructive in the extreme. In the Northern Ethnography chapter he describes why “the feeling of belonging to the family of all Arctic peoples is essential... They now call themselves the Fourth World and demand their place in the international community.”

Earlier in the book he argues that cultures of the Arctic must be understood as “the cradle of shamanism” since the word saman comes from the vocabulary of the Mandchu-Tungusic languages in Siberia. He distinguishes between the circumpolar peoples’ shamanism, and cultures which have similar, comparable phenomena, and non-shamanic cultures such as African and Near Eastern spirit possession creeds.

The difference between established and ethnic religion puts us on the path of defining shamanism, according to Pentikäinen. Established religions, with the exception of Indian Hinduism, “have been stamped with the personality of a historical figure” such as Mohammed, Zarathustra, Jesus Christ. In contrast to these missionary religions, ethnic religions evolved without a founder and are “linked to the ecological environment temporally, spatially, and socially.” In other words, ethnic religions are local.

But can shamanism even be called a religion?, Pentikäinen asks. “Shamanism is not a ‘religion’ but rather a ‘world-view system’ or a ‘grammar of mind’ having many intercorrelations with ecology, economy, social structure...”

Pentikäinen goes so far as to abandon “shamanism” altogether, replacing the term with shamanhood. Part of shamanhood, he points out, belongs to the whole extended family, the siidra: “... a way of living, experiencing, feeling Sami existence as an individual human being and as a society, close to nature in what to outsiders often appear as isolated small communities. All this has existed in the human mind without being called a religion.”

About a hundred cultures have so far survived in the circumpolar regions, none of whom “ever had a native concept of ‘religion’,” Pentikäinen emphasizes.

That the United Nations declares a Year of the Indigenous People is further indication of a growing sentiment against colonization in all its forms. Even in academia it’s accepted now that cultural diversity is important, ever more so in this age of globalization. To wit: the work of Juha Pentikäinen, since 1972 department chair of comparative religion at a Helsinki university, and also well-known as visiting professor at universities in California, Indiana, Minnesota, Texas. His extensive research investigates the circumpolar peoples in Sápmi and in the Russian arctic. He writes with an authoritative voice, having undertaken over 20 journeys to interview, and interact with, shamans, including one of the Khanty in Siberia when the weather was “cold” – minus 42 degrees Celsius.

In Shamanism and Culture (© 2006) Pentikäinen analyzes what Russia’s oil and gas industries are doing to indigenous lives and cultures, destructive in the extreme. In the Northern Ethnography chapter he describes why “the feeling of belonging to the family of all Arctic peoples is essential... They now call themselves the Fourth World and demand their place in the international community.”

Earlier in the book he argues that cultures of the Arctic must be understood as “the cradle of shamanism” since the word saman comes from the vocabulary of the Mandchu-Tungusic languages in Siberia. He distinguishes between the circumpolar peoples’ shamanism, and cultures which have similar, comparable phenomena, and non-shamanic cultures such as African and Near Eastern spirit possession creeds.

The difference between established and ethnic religion puts us on the path of defining shamanism, according to Pentikäinen. Established religions, with the exception of Indian Hinduism, “have been stamped with the personality of a historical figure” such as Mohammed, Zarathustra, Jesus Christ. In contrast to these missionary religions, ethnic religions evolved without a founder and are “linked to the ecological environment temporally, spatially, and socially.” In other words, ethnic religions are local.

But can shamanism even be called a religion?, Pentikäinen asks. “Shamanism is not a ‘religion’ but rather a ‘world-view system’ or a ‘grammar of mind’ having many intercorrelations with ecology, economy, social structure...”

Pentikäinen goes so far as to abandon “shamanism” altogether, replacing the term with shamanhood. Part of shamanhood, he points out, belongs to the whole extended family, the siidra: “... a way of living, experiencing, feeling Sami existence as an individual human being and as a society, close to nature in what to outsiders often appear as isolated small communities. All this has existed in the human mind without being called a religion.”

About a hundred cultures have so far survived in the circumpolar regions, none of whom “ever had a native concept of ‘religion’,” Pentikäinen emphasizes.

He points out that the indigenous of Russia’s north have the closest connection to their shamanic traditions. “The atheistic Soviet revolution set back the mission religions which had reached Arctic areas. As churches were closed and priests were killed the institutions depending on them were also broken... (Indigenous) religions were deep-frozen for a couple of generations and thus saved from the ideological changes that followed Western civilization, organized education or americanization not only in the New World but also in the Scandinavian countries.”

Today’s revival of shamanism is a link to ethnic revival, he notes. “At present shamanism is gaining recognition as an integral part of the northern identity.” However, ethnic survival and revival are possible only when ethnic language is alive. Pentikäinen refers to a 1989 census taken in Russia, which lists 26 indigenous groups and the percentage of their population who speak in native tongue. In six of the ethnic groups, native speakers ranged from 85.9 to 57.8 percent; nine groups had 54.8 to 44.7 percent native speakers; in the rest of the groups native language had declined to under 40 percent. Pentikäinen projects the first group’s ethnic survival chances to be good, the middle group’s ethnic survival he judges “possible... if effective measures are taken very soon,” but he holds out little hope for the below-40-percent group.

Among the demands put forth by the Khanty during the Glasnost period of the Soviet Union, as quoted by Pentikäinen, a break from the aforementioned “organized education” stands out: “The indigenous inhabitants must be allowed to decide on the kind of school they want for their children.”

This seems to tie in with a musing of Johan Utsi the Sámi: “My father never knew what ecology was. He was simply part of it. I know what ecology is. But I am no longer part of it.”

Today’s revival of shamanism is a link to ethnic revival, he notes. “At present shamanism is gaining recognition as an integral part of the northern identity.” However, ethnic survival and revival are possible only when ethnic language is alive. Pentikäinen refers to a 1989 census taken in Russia, which lists 26 indigenous groups and the percentage of their population who speak in native tongue. In six of the ethnic groups, native speakers ranged from 85.9 to 57.8 percent; nine groups had 54.8 to 44.7 percent native speakers; in the rest of the groups native language had declined to under 40 percent. Pentikäinen projects the first group’s ethnic survival chances to be good, the middle group’s ethnic survival he judges “possible... if effective measures are taken very soon,” but he holds out little hope for the below-40-percent group.

Among the demands put forth by the Khanty during the Glasnost period of the Soviet Union, as quoted by Pentikäinen, a break from the aforementioned “organized education” stands out: “The indigenous inhabitants must be allowed to decide on the kind of school they want for their children.”

This seems to tie in with a musing of Johan Utsi the Sámi: “My father never knew what ecology was. He was simply part of it. I know what ecology is. But I am no longer part of it.”

*****

Finland: its high north is covered by extensive forest of pine and other conifers and birch, birch clearly the evolutionary big winner across Fennoscandia. Most of the forest does not grow dense but invites hiking. Modest little shrub forms the understory, much of it bearing berries in summer. The fells aren’t as tall and steep as we saw them in Swedish Sápmi, they rise up from the taiga not in a chain but as individual heights. Lakes large and small invite fishing; rivers mostly appear slow, solemn, dark flows. Through the trees we espy a home every so often, set off from the highway, but overall the countryside is very sparsely populated, less than one person per square kilometer according to the statistics. Numerously dense are the mosquitoes, flies, wasps – of insects there are literally billions on days when atmospheric conditions favor their bloodsucking activities.

Photo by Miina Sanila

Photo by Miina Sanila A few miles from the northeast tip of Finland we spot a sign to a reindeer farm; down a gravel road we come to a spacious café with free WIFI and nice sauna (of course, this is Finland). They have cabins they’re renting by day and week. One reason we decide to stay awhile is that at all those Sámi museums we visited, hardly any of the staff are actually Sámi. We want to get to know the Sámi a little.

Let us tell you: nobody makes better fish soup than these Sámi. Nobody.

Or is it Miina Sanila’s kitchen magic in particular that cooks fish into such heavenly flavors? In any case, fishing is central to Sámi traditions, Sanila tells us after she returns from a fishing trip on a big river where her mother, Toini Sanila, owns a backwoods cabin. She shows us photos on her cell phone, relating that she's gone on salmon fishing trips since she can remember. "It's a family gathering, children participate and get excited."

Let us tell you: nobody makes better fish soup than these Sámi. Nobody.

Or is it Miina Sanila’s kitchen magic in particular that cooks fish into such heavenly flavors? In any case, fishing is central to Sámi traditions, Sanila tells us after she returns from a fishing trip on a big river where her mother, Toini Sanila, owns a backwoods cabin. She shows us photos on her cell phone, relating that she's gone on salmon fishing trips since she can remember. "It's a family gathering, children participate and get excited."

Photo by Miina Sanila

Photo by Miina Sanila The salmon are caught in a net hung from a row boat. This fishing method is allowed for locals during certain periods in summer. The net needs to be cleaned every three hours. The fish in the photo, an 11-kilogram! salmon, was caught after the net had been in the water for 20 hours, Sanila says.

Fishing is relevant for the Sami throughout the year. In winter they ice-fish for char, also with nets. Whitefish and grayling are fished for in spring. "We sometimes also go to the Norwegian side, to fish in the ocean there and to catch king crab," she says.

Fishing is relevant for the Sami throughout the year. In winter they ice-fish for char, also with nets. Whitefish and grayling are fished for in spring. "We sometimes also go to the Norwegian side, to fish in the ocean there and to catch king crab," she says.

Her mother's reindeer graze on a large reach of taiga and lakes where about 30 people have claim on altogether 3600 reindeer. "There is a summer area for the deer, and a winter area." Each family has a certain pattern of notching their reindeers' ears, by which marking the ownership is established. "In some areas the ear-marking gets done around the Midsummer Festival (June 20). After that it's holiday, although some people grow hay that gets cut and dried and put up loose in big barns, in summer."

Between September and January the reindeer round-ups are held. "Reindeer grow very quickly in the summer, they eat almost anything that's green. Mostly the male calves are used for meat. Also some of the older animals. The reindeer get taken to a local slaughterhouse. Some of the meat gets transported from there to processing plants of large companies. But some people make meat products themselves (such as jerky), to sell and make a little more money."

Reindeer range freely in the forest, they're shy; however, the males can be very aggressive to humans during their rut in autumn. "By then they have very massive antlers," Sanila notes.

Every day we see reindeer wander among the visitor cabins. This is not normal reindeer behavior, Sanila notes. “They hang around because my aunt feeds them.”

As we watch the reindeer, we find their antlers striking, they’re so much larger than those of deer, they seem almost over-sized. And that clicking sound their legs make, that does seem strange.

In Toini Sanila’s restaurant hang old photographs; one black-and-white image shows a Sámi skijoring behind a reindeer. But Miina Sanila says that's rare today. "I have sat in a reindeer sled, but since the snow-scooters (snowmobiles) came in the 1960s, very few people train reindeer for pulling. It's very hard work to train the reindeer." Sámi dogs are still traditionally used in herding.

Snowmobiles, cars, houses, roads, electricity, TV, WIFI – clearly this is modern life of the Sámi. They appear to navigate through our technology-spangled era using their culture as a rudder to keep their ethnic identity; after all, culture is not a stagnant thing. Meanwhile they spent a lot of time outdoors. For Sanila and her Sámi boyfriend it's important to protect, and nurture, Sámi culture. "Our language is the most in danger," she comments.

There are nine different Sámi languages, she points out. Traditions, myths, customs and costumes vary considerably between the groups of Sámi speakers. Whereas Sweden and Norway Sámi are distinctly apart from the rest of each nation’s population, racially, and some regulations are specific to the Sámi – “only Sámi are allowed to become reindeer managers there” –, in Finland the lines blur because Finns and Sámi are rather closely related. (The Finnish word for Finland is Suomi.) A schematic of the Uralic languages shows the “Saami dialects” developing from “Primitive Saami” which is dated 1000 BC to 700 AD, preceded by “Early Primitive Finnish” 1500 BC to 1000 BC; the “Late Primitive Finnish,” after the Saami branched off, dates 1000 BC to 0 and ends up as Finnish, Karel, Vespe, Vote, Estonian and Livonian.

The original religion of the Sámi has the Sun as the father of the Sámi, the Earth as their mother, Sanila explains. The sense of belonging to the Earth is strong to this day, she emphasizes. "When a mine was planned near here, the Skolt Sami people held a lot of meetings, and in the end the mine didn't happen. But not long ago diamonds were looked for in the adjacent Utsjoki area, so maybe someone will want to start digging for diamonds. But we Sámi don't want diamonds, we love our land because it's the beginning of life."

Many Sámi belong to Christian churches today, mostly the Lutheran Church. The Skolt Sámi, to whom the Sanilas belong, traditionally lived farther to the east, on lands the Russians took during the "Winter War" between Soviet Russia and Finland in 1939-1940. That’s when the Finnish government resettled the Skolt Sámi on the Finnish side of the border. Many Skolt Sámi adhere to Russian-Orthodox religion.

Is any of their old nature religion still alive? "We still use drums, but for music, and parts of reindeer hooves for shakers. We also still have a game that children and adults play, using the leg bones of reindeer. Playing that game is a lot of fun," Sanila says.

Are there still Sámi shamans? She hesitates. “No.”

The extend of cultural connection with their past seems to be in a flux. We get the sense that pride in Sámi culture is about to be saved, savored, in a just-in-time manner: Sanila says that people of the older generation, such as her boyfriend's 76-year-old father, still speak of "Lapland" and "Lappish" language. "In the 1960s-1970s it changed officially to where it's called Sámi-Land and people are called sámi people after that."

Between September and January the reindeer round-ups are held. "Reindeer grow very quickly in the summer, they eat almost anything that's green. Mostly the male calves are used for meat. Also some of the older animals. The reindeer get taken to a local slaughterhouse. Some of the meat gets transported from there to processing plants of large companies. But some people make meat products themselves (such as jerky), to sell and make a little more money."

Reindeer range freely in the forest, they're shy; however, the males can be very aggressive to humans during their rut in autumn. "By then they have very massive antlers," Sanila notes.

Every day we see reindeer wander among the visitor cabins. This is not normal reindeer behavior, Sanila notes. “They hang around because my aunt feeds them.”

As we watch the reindeer, we find their antlers striking, they’re so much larger than those of deer, they seem almost over-sized. And that clicking sound their legs make, that does seem strange.

In Toini Sanila’s restaurant hang old photographs; one black-and-white image shows a Sámi skijoring behind a reindeer. But Miina Sanila says that's rare today. "I have sat in a reindeer sled, but since the snow-scooters (snowmobiles) came in the 1960s, very few people train reindeer for pulling. It's very hard work to train the reindeer." Sámi dogs are still traditionally used in herding.

Snowmobiles, cars, houses, roads, electricity, TV, WIFI – clearly this is modern life of the Sámi. They appear to navigate through our technology-spangled era using their culture as a rudder to keep their ethnic identity; after all, culture is not a stagnant thing. Meanwhile they spent a lot of time outdoors. For Sanila and her Sámi boyfriend it's important to protect, and nurture, Sámi culture. "Our language is the most in danger," she comments.

There are nine different Sámi languages, she points out. Traditions, myths, customs and costumes vary considerably between the groups of Sámi speakers. Whereas Sweden and Norway Sámi are distinctly apart from the rest of each nation’s population, racially, and some regulations are specific to the Sámi – “only Sámi are allowed to become reindeer managers there” –, in Finland the lines blur because Finns and Sámi are rather closely related. (The Finnish word for Finland is Suomi.) A schematic of the Uralic languages shows the “Saami dialects” developing from “Primitive Saami” which is dated 1000 BC to 700 AD, preceded by “Early Primitive Finnish” 1500 BC to 1000 BC; the “Late Primitive Finnish,” after the Saami branched off, dates 1000 BC to 0 and ends up as Finnish, Karel, Vespe, Vote, Estonian and Livonian.

The original religion of the Sámi has the Sun as the father of the Sámi, the Earth as their mother, Sanila explains. The sense of belonging to the Earth is strong to this day, she emphasizes. "When a mine was planned near here, the Skolt Sami people held a lot of meetings, and in the end the mine didn't happen. But not long ago diamonds were looked for in the adjacent Utsjoki area, so maybe someone will want to start digging for diamonds. But we Sámi don't want diamonds, we love our land because it's the beginning of life."

Many Sámi belong to Christian churches today, mostly the Lutheran Church. The Skolt Sámi, to whom the Sanilas belong, traditionally lived farther to the east, on lands the Russians took during the "Winter War" between Soviet Russia and Finland in 1939-1940. That’s when the Finnish government resettled the Skolt Sámi on the Finnish side of the border. Many Skolt Sámi adhere to Russian-Orthodox religion.

Is any of their old nature religion still alive? "We still use drums, but for music, and parts of reindeer hooves for shakers. We also still have a game that children and adults play, using the leg bones of reindeer. Playing that game is a lot of fun," Sanila says.

Are there still Sámi shamans? She hesitates. “No.”

The extend of cultural connection with their past seems to be in a flux. We get the sense that pride in Sámi culture is about to be saved, savored, in a just-in-time manner: Sanila says that people of the older generation, such as her boyfriend's 76-year-old father, still speak of "Lapland" and "Lappish" language. "In the 1960s-1970s it changed officially to where it's called Sámi-Land and people are called sámi people after that."

*****

One day Sanila’s sister, Tiina Sanila-Aikio, arrives for a visit with her small daughter. She readily agrees to be interviewed, our chance to hear the views of a Sámi politician: Sanila-Aikio was elected to the Sámi Parliament at Inari for a four-year term that she started serving in 2012. Meeting four times a year, the parliament consists of 21 members, seven of whom are women, and there are also four substitutes. It was established in 1996. “Before then there was a similar body (of council), that’s existed since the 1970s.”

Politically, the Sámi’s power is “quite minimal,” Sanila-Aikio acknowledges. “Our parliament is not part of the state government. Some issues we discuss with the minister of justice.” Mostly, Sámi matters are still controlled by Helsinki politicians. Even the state government’s definition of which persons count as Sámi, is a bone of contention at Inari. “There are only 10,000 of us, so everybody knows who’s Sámi,” she remarks.

Their small size in number often goes against them in national elections where the Sámi voice is hardly heard. The recurring big issue is how resource-based economics are presented to the voting public, in view of the fact that mining and timber generate a whole lot more taxes for the government than does reindeer herding; besides, government investment is proportionately small when international mining corporations get involved. “When money talks, it talks,” Sanila-Aikio puts it.

“We had a catastrophe at a mine that caused fish to die in a radius of hundreds of kilometers. So, at the moment, Finland is trying to sell us on the idea of ‘green mining’.” Looking further afield, she expresses concern over a big chunk of the circumpolar region: “We’re very worried about what’s happening (industrially) in the Russian arctic.”

Politically, the Sámi’s power is “quite minimal,” Sanila-Aikio acknowledges. “Our parliament is not part of the state government. Some issues we discuss with the minister of justice.” Mostly, Sámi matters are still controlled by Helsinki politicians. Even the state government’s definition of which persons count as Sámi, is a bone of contention at Inari. “There are only 10,000 of us, so everybody knows who’s Sámi,” she remarks.

Their small size in number often goes against them in national elections where the Sámi voice is hardly heard. The recurring big issue is how resource-based economics are presented to the voting public, in view of the fact that mining and timber generate a whole lot more taxes for the government than does reindeer herding; besides, government investment is proportionately small when international mining corporations get involved. “When money talks, it talks,” Sanila-Aikio puts it.

“We had a catastrophe at a mine that caused fish to die in a radius of hundreds of kilometers. So, at the moment, Finland is trying to sell us on the idea of ‘green mining’.” Looking further afield, she expresses concern over a big chunk of the circumpolar region: “We’re very worried about what’s happening (industrially) in the Russian arctic.”

The Sámi lifestyle based on reindeer management is at stake at every intrusion, for the clear reason that the animals need large areas of habitat. But the Sámi are learning how to keep the wolf from the door: “About 10 years ago there was a ‘forest fight’,” Sanila-Aikio relates. “My husband’s reindeer community negotiated so long with the timber company without reaching an agreement, the timber company got frustrated and gave up.”

In some of their environmental defense tactics Green Peace got involved. “But in some cases that divides the (local) community,” she remarks.

The new deal that government and timber industry propose is a “forest certificate” for what’s supposed to be ecologically conscientious logging, a plan that many Sámi view with suspicion, she says.

As for dams, “not ever again!,” Sanila-Aikio exclaims. “In the 1950s and 1960s they made a new lake, we know better now.”

The Achilles heel of Sámi communities and of the Sámi parliament is that “the Finnish state owns the land,” she reiterates.

What of the European Union, any support for the Sámi from those quarters? (Finland is a member of the EU, and of the Eurozone.) “A year ago we had our plenum in Brussels (where the EU parliament is). We didn’t get anywhere with the EU because we don’t know how to work the system.” (Which is very much based on lobbying.) “We are pressuring the Finnish government to give us more of the funds they’re getting from the EU.”

But the United Nations, well, at least in spirit they’re throwing support to all indigenous peoples when they have their Indigenous Peoples’ Conferences. They boost morale, Sanila-Aikio relates, adding that she’s been to such a conference in New York: “It was great to meet other indigenous people. For me it was especially interesting to talk with some of the Native Americans who attended.”

This September she was scheduled to be in New York for the next UN event focused on indigenous peoples.

In some of their environmental defense tactics Green Peace got involved. “But in some cases that divides the (local) community,” she remarks.

The new deal that government and timber industry propose is a “forest certificate” for what’s supposed to be ecologically conscientious logging, a plan that many Sámi view with suspicion, she says.

As for dams, “not ever again!,” Sanila-Aikio exclaims. “In the 1950s and 1960s they made a new lake, we know better now.”

The Achilles heel of Sámi communities and of the Sámi parliament is that “the Finnish state owns the land,” she reiterates.

What of the European Union, any support for the Sámi from those quarters? (Finland is a member of the EU, and of the Eurozone.) “A year ago we had our plenum in Brussels (where the EU parliament is). We didn’t get anywhere with the EU because we don’t know how to work the system.” (Which is very much based on lobbying.) “We are pressuring the Finnish government to give us more of the funds they’re getting from the EU.”

But the United Nations, well, at least in spirit they’re throwing support to all indigenous peoples when they have their Indigenous Peoples’ Conferences. They boost morale, Sanila-Aikio relates, adding that she’s been to such a conference in New York: “It was great to meet other indigenous people. For me it was especially interesting to talk with some of the Native Americans who attended.”

This September she was scheduled to be in New York for the next UN event focused on indigenous peoples.

*****

When our conversation turns to culture, Sanila-Aikio addresses the balance between assimilation and cultural identity. “We’re one nation spread over four different countries. It’s quite rare that a group speaks 100 percent Sámi. One of the most important things is that Sámi culture can change with the world, and we would like much more influence over how that change happens.”

In her personal life she’s pursuing one way to spread ethnic awareness. After studying law she became a teacher at the Sámi Educational School, a vocational school where her students’ age is spread from 17 to 67 years. Her small daughter already speaks two Sámi languages.

Yet the thread back to old Sámi traditions is very thin, she remarks. “The Lutheran Church ruined a lot. For a long time even yoiking was forbidden. (To yoik is a Sámi way of singing/chanting).”

We remember how her sister had hesitated when we asked about shamans, and pressure Sanila-Aikio to be more forthcoming. “OK,” she says, “we have people who can heal. But they don’t do it in public. There are also people who drum and yoik, and some who go to holy rocks for luck in hunting. But that part of Sámi culture is very, very intimate, it stays within a circle of trust, among people who’ve known each other for a long time.”

One more question: the fly agaric mushroom, do the Sámi make use of it? A definite “No” from Sanila-Aikio adds to the mystery, since neither Juha Pentikäinen nor John Utsi so much as mention the hallucinogenic in their writings we’ve read. Whereas the agaric features famously in the published research of Aldous Huxley and several others of his generation, particularly in conjunction with shamanic trances.

We’ll have to leave it at the drumming.

In her personal life she’s pursuing one way to spread ethnic awareness. After studying law she became a teacher at the Sámi Educational School, a vocational school where her students’ age is spread from 17 to 67 years. Her small daughter already speaks two Sámi languages.

Yet the thread back to old Sámi traditions is very thin, she remarks. “The Lutheran Church ruined a lot. For a long time even yoiking was forbidden. (To yoik is a Sámi way of singing/chanting).”

We remember how her sister had hesitated when we asked about shamans, and pressure Sanila-Aikio to be more forthcoming. “OK,” she says, “we have people who can heal. But they don’t do it in public. There are also people who drum and yoik, and some who go to holy rocks for luck in hunting. But that part of Sámi culture is very, very intimate, it stays within a circle of trust, among people who’ve known each other for a long time.”

One more question: the fly agaric mushroom, do the Sámi make use of it? A definite “No” from Sanila-Aikio adds to the mystery, since neither Juha Pentikäinen nor John Utsi so much as mention the hallucinogenic in their writings we’ve read. Whereas the agaric features famously in the published research of Aldous Huxley and several others of his generation, particularly in conjunction with shamanic trances.

We’ll have to leave it at the drumming.

*****

We’re scheduled to catch the celebrated Hurtigruten ship from Kirkenes, Norway. As we say our good byes to the Sanilas, we reflect on where the Sámi stand in Europe. In all the rest of Europe, people lost their bond to their long-ago ancestry when church and aristocracy, then church and territorial state, then industrialism and nationalism built the walls of civilization ever higher. The accumulating changes in social structure removed the people so far from the natural state in which their forebears lived, that wilderness became a fright to them. Conversely, the Sámi still hold on to a continuity that is, however tenuous, like a limb from the Stone Age. Which is probably wise, seeing how civilizations have utterly failed in attaining any sort of sustainability. The Sámi blend of modern world with all its accoutrements, and perseverance in some of their old ways of relating to nature, makes them very special. They’re a lucky people in their vast circumpolar region.

Strictly speaking, the reindeer farm of Toini Sanila belongs in the category of hospitality industry. But it doesn’t take long before you realize it isn’t an “industry” at all. Early on, when we found out that Miina was Toini Sanila’s daughter, we assumed that the other two young people working at the place were her children, too, judging by how they were treated. But no. They’re two young locals with a seasonal job which they’re doing very efficiently. And it was more than Toini Sanila mothering them, it was a kindness in the atmosphere. We also noticed this when locals came by for a social visit, always sitting on the table not decked out next to the bar, always calm and friendly.

Now we’re reminded of what Miina Sanila told us when she was talking of Finns who’d moved into the area: “The Finns here,” she’d said, “many times adapt to the Sámi way. Nature makes you do that.”

Strictly speaking, the reindeer farm of Toini Sanila belongs in the category of hospitality industry. But it doesn’t take long before you realize it isn’t an “industry” at all. Early on, when we found out that Miina was Toini Sanila’s daughter, we assumed that the other two young people working at the place were her children, too, judging by how they were treated. But no. They’re two young locals with a seasonal job which they’re doing very efficiently. And it was more than Toini Sanila mothering them, it was a kindness in the atmosphere. We also noticed this when locals came by for a social visit, always sitting on the table not decked out next to the bar, always calm and friendly.

Now we’re reminded of what Miina Sanila told us when she was talking of Finns who’d moved into the area: “The Finns here,” she’d said, “many times adapt to the Sámi way. Nature makes you do that.”

*****

When we get to Kirkenes, a small port city located on the very northeast tip of Norway on the border with Russia, we come upon yet another Sámi mystery. Archeologists found two stone labyrinths in the area which, according to some researchers, are from the Stone Age; other scientists date them more recently. In any case these labyrinths are old, and what raises all kinds of speculation is the concentric pattern in which the stones are placed. Archeologists call the pattern “Cretan” labyrinth, because the very same labyrinth design appears on an ancient coin found in Knossos on the Greek island Crete.

Was there a connection between the Greeks and the Sámi at some juncture? Strangely enough, the Greeks gave us the word Arctic which is derived from arctos, bear; in Sámi culture of old the bear was an animal with special spirit powers, they did hunt the bear but in a ritual that required the animal’s bones to be buried in such a way that they formed an anatomically correct skeleton in the grave. Both, the Greeks and the Sámi, put the Bear in the night sky as a starry constellation.

Back to the labyrinth: the same Cretan pattern appears in floor mosaic patterns in Pompei, Italy, which may not be much of a surprise considering the ties between Greek and Roman cultures; but that the Hopi of Arizona would carve Cretan labyrinths on rock surely is puzzling.

An explanation for the Kirkenes and other arctic labyrinths evades us. Some archeologists reason that, since the labyrinths are in proximity to burial grounds, they were erected for funeral ceremonies. Others hypothesize that, since the labyrinths are found only near the coast, the myths of sea serpents played a role; perhaps the labyrinths were built for rites meant to appease the fjord monsters.

We glance at the arctic waters of the Varangerfjord and see no serpents, but the Hurtigruten (“Fast Route”) ship is approaching to take us away. One of 11 Hurtigruten ships along Norway’s coastline connecting Kirkenes with Bergen, the liner is a ferry - mail boat - cruise ship hybrid. It calls on over 30 ports during the six-day sea sojourn. The coast is always in view; much of the time we pass through archipelagoes strewn before fjords that reach far into mountainous topography.

Was there a connection between the Greeks and the Sámi at some juncture? Strangely enough, the Greeks gave us the word Arctic which is derived from arctos, bear; in Sámi culture of old the bear was an animal with special spirit powers, they did hunt the bear but in a ritual that required the animal’s bones to be buried in such a way that they formed an anatomically correct skeleton in the grave. Both, the Greeks and the Sámi, put the Bear in the night sky as a starry constellation.

Back to the labyrinth: the same Cretan pattern appears in floor mosaic patterns in Pompei, Italy, which may not be much of a surprise considering the ties between Greek and Roman cultures; but that the Hopi of Arizona would carve Cretan labyrinths on rock surely is puzzling.

An explanation for the Kirkenes and other arctic labyrinths evades us. Some archeologists reason that, since the labyrinths are in proximity to burial grounds, they were erected for funeral ceremonies. Others hypothesize that, since the labyrinths are found only near the coast, the myths of sea serpents played a role; perhaps the labyrinths were built for rites meant to appease the fjord monsters.

We glance at the arctic waters of the Varangerfjord and see no serpents, but the Hurtigruten (“Fast Route”) ship is approaching to take us away. One of 11 Hurtigruten ships along Norway’s coastline connecting Kirkenes with Bergen, the liner is a ferry - mail boat - cruise ship hybrid. It calls on over 30 ports during the six-day sea sojourn. The coast is always in view; much of the time we pass through archipelagoes strewn before fjords that reach far into mountainous topography.

For us it was a memorable way to see Sápmi fade away. The first days of the trip brought us to the harbors of small villages with fishing boats; in one port a huge graffiti: “Cod Is Great.” Whenever the ship’s at a dock, fresh food stuffs were loaded into the belly of the vessel, an astounding variety of seafood as well as local berries ripe and scrumptious, and fresh vegetables farmed along the coast. The arctic may appear raw and forlorn, but the meals in the ship’s fine restaurant prove this appearance wrong with a cornucopia of excellent cuisine locally sourced along the route.

The farther south, the larger the villages; still farther on, towns. When the ship’s intercom announces that we’re crossing the Polar Circle, passengers hurry on deck to see the monument on a small isle marking the latitude, a metal representation of the globe’s latitudes and longitudes.

When we arrive at Bergen we know we’ve left Sápmi behind: Bergen’s a big city, holding forth its proud history as outpost of the Hanseatic League. The contrast to Sápmi couldn’t be greater.

The farther south, the larger the villages; still farther on, towns. When the ship’s intercom announces that we’re crossing the Polar Circle, passengers hurry on deck to see the monument on a small isle marking the latitude, a metal representation of the globe’s latitudes and longitudes.

When we arrive at Bergen we know we’ve left Sápmi behind: Bergen’s a big city, holding forth its proud history as outpost of the Hanseatic League. The contrast to Sápmi couldn’t be greater.

*****

We don’t write poetry but we’ll take poetic license and return to the Bäckerei just when Lentz takes the last bite of her Bienenstich. As we re-enter the German timeline post-Middle Ages, a horrendous period lies before us, horrendous for German farmers especially.

It’s a good thing that Lentz has fortified herself with rye, spelt, wheat – and a whole load of sugar.

It’s a good thing that Lentz has fortified herself with rye, spelt, wheat – and a whole load of sugar.

© 2014 Lentz Spelt Farms

* Next time you’re in Finland, we strongly recommend you visit Reindeer Farm Toini Sanila: www.sanila.fi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed